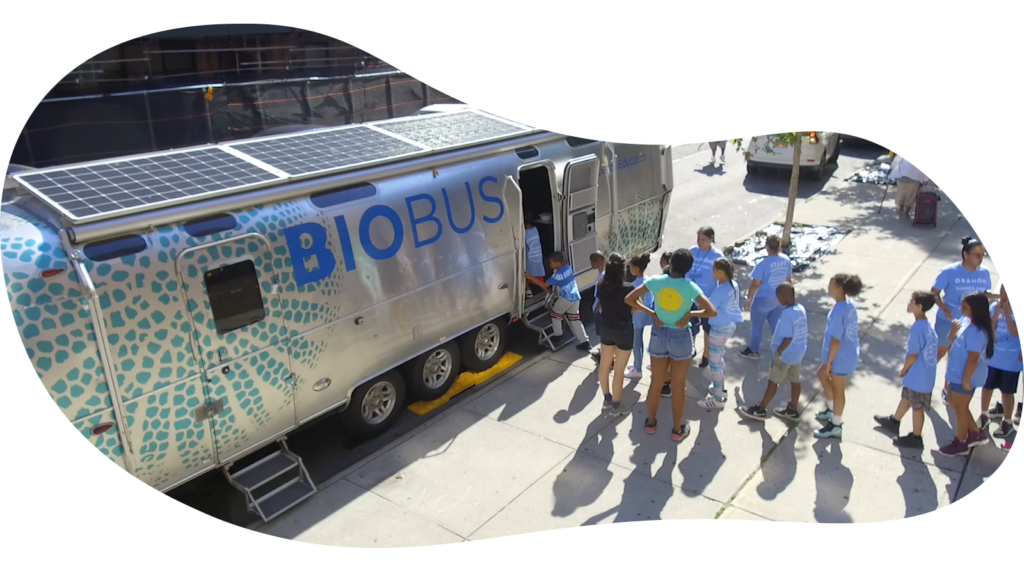

In 2008, a colorful bus rolled into New York City’s Lower East Side. Its goal was to transport K-12 and college students in communities historically excluded from science to a microscopic world of wonder — an experience that would put them on the road to becoming scientists themselves. BioBus, as it would come to be known, was its own experiment, thought up by scientist Ben Dubin-Thaler, after completing his Ph.D. in Biology at Columbia University. His hypothesis was that anyone could be excited and inspired by science, if only they were given the chance to perform hands-on biology experiments using research-grade microscopes. BioBus would meet untapped communities where they were at, and help children develop their own science identities. The activist-teachers have advanced this mission for the past 14 years, ever expanding their scope. At this point, the project has expanded into two mobile labs, a litany of school, weekend and summer programs, and reached over 300,000 students all across New York City.

As a former postdoc at Johns Hopkins University and Weill Cornell Medical Center, BioBus’s Chief Science Officer Latasha Wright knows a thing or two about reaching your scientific potential. For over a decade, she has been an advocate for science inclusivity, helping design programs for and by untapped communities. As any grassroot organizer will tell you, there is no substitute for direct, lasting engagement — living there, being there, sharing the same experiences. That’s how you build trust in a community. That trust has gone a long way for BioBus, embedding them in many New York neighborhoods so much so that brothers, sisters and cousins from the same families have participated in their programs.

The value of this kind of work has only become clearer since 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic brought the world to a standstill and demanded a high level of scientific literacy from the general public. Suddenly, science in the media exploded and regular people needed to understand terminology like ‘receptor,’ ‘mRNA’ and ‘viral load.’ BioBus has been navigating this complex path for years. Earlier this month, I sat down with Latasha to learn more about her team’s unique approach to this evermore crucial challenge.

Yewande Pearse: Like all great science, BioBus started with a clear hypothesis: ‘Giving people hands-on experience in an authentic research environment will empower them to embrace and practice science.’ What were your early experiences of trying that out, when BioBus was literally still just a 1974 transit bus fresh off Oregon craigslist?

Latasha Wright: Our goal from the outset was to lower the threshold for accessibility. The mobile science lab allowed us to bring an authentic research experience to all parts of New York city. What we found was that there was a huge thirst for science in every school we visited. This interest wasn’t determined by where the students were from but by how the science was presented. If science was shown to be something wonderful, something to engage their curiosity, something that allows them to ask questions, to see things through these cool microscopes that they hadn’t seen before, almost everyone was super-engaged and wanted more. We proved that science can be accessible and pertinent to everyone, every day.

Yewande Pearse: That’s quite the departure from my memories of science class at school [in England]. We spent a lot of time doing things with potatoes.

Latasha Wright: Our experiments started simply too. When it was raining outside, we would take the students out on the street with their pipettes to sample some water and then look at it under a microscope — or the soil outside of their schools. They got to see the microbial life all around them in the unseen world. It’s such a mystery at first and turns out to be so beautiful. Many of them were, like, “I love this, and I want to do more.” That’s when we started really trying to start our community labs for kids to come and do more in-depth programming.

Yewande Pearse: You’ve brought that in-depth programming into schools all over New York. How do the teachers respond to this outside help?

Latasha Wright: We have a list of NYC standards-aligned curriculums that they can choose from but it’s mostly inquiry-driven and curiosity-driven, so the kids can come aboard and follow their passions. I like to describe it as, we’re that fun aunt, you know? We have a curriculum that’s our bread and butter, but the course of teaching is driven by the students’ questions — what they really want to know. We can do things that the teachers can’t do. If the kids want to see some poop, we can say “let’s talk about poop!” The students can engage with us on a different level than their teachers because they’re not seeing us every day, we’re new, we have no preconceived notions about if they’re a good kid or bad kid. We’re just trying to engage them and make science alive and accessible to them.

Yewande Pearse: I love that: curiosity-driven science. You’re exploring the mystery of life together.

Latasha Wright: That’s what’s great about the microscopes. You can see all the way down to the deepest level of an organism. Sometimes we use this thing called Daphnia, a small crustacean. When you look at it in suspension it’s this little white thing you can hardly see, but then when you put it under the microscope it becomes this transparent organism that has a heart, a shell, legs. It gets students saying, “Oh, even though I can barely see this thing, it has all these organs. It is, in fact, very similar to me.” Then you can zoom in to see individual cells, and then you can even use the electron microscopy and start seeing the bacteria on top of the cells.

We started to see ourselves as a bridge not only to science but to public health.

Yewande Pearse: I remember reading a story in the New York Times about how scientists were first able to glimpse the SARS-CoV-2 virus. They concentrated some virus-laden fluid to a single drop then froze it and used a cryo-electron microscope, which fired beams of electrons at the sample to visualize it. As the electrons bounced off the atoms inside, a computer reconstructed what the microscope had seen forming a picture. They could see thousands of intact coronaviruses packed in the ice, allowing them to inspect details on the viruses that measured less than a millionth of an inch. Now, it’s not just the scientific community who need to understand the Coronavirus, but all of us. How has BioBus served as a conduit to science literacy during COVID’s many overlapping phases — from the outbreak, to collective mitigation, to mass vaccination — while also dealing with the impact of the pandemic?

Latasha Wright: Like everybody, we had a bit of an identity crisis when Covid hit because we always thought of the hands-on, IRL experience as our bread and butter. But we knew that we had to serve our communities because we were scientists and we wanted to make sure that people understood what was going on — that people felt like they could go to someone who they had built a relationship with, who they could trust. That’s how we started the Student Town Hall series. Parents and teachers could send in their questions and then professional scientists would answer them. Our first Town Hall was right at the beginning of Covid, in March 2020, and drew almost a thousand people. We were the first outfit to really do that format. We talked about Covid, what it was, what kind of virus it was and how it was transmitted. We would talk about the droplets and why you need to be safe and what you need to do to be safe using the information that we had at the time. We also had elected officials come in and the kids could ask them questions. We started to see ourselves as a bridge not only to science but to public health.

Yewande Pearse: How did you adapt your expansive learning program to online students learning from home?

Latasha Wright: All our scientists got microscopes at their house and were set up to be able to Zoom into school classrooms. We made up these theme challenges where students could watch a short video and then do an experiment at home using materials that they could find around their house. We also had the Town Halls once a week, and kept working with our high school and college interns. They started doing science communication stuff. A lot of them made videos about the science of Covid, or mental health during the pandemic. It was a way for them to talk to their communities about what was going on.

Yewande Pearse: I really like the idea of BioBus as a steward of science, and how it allows kids to carry the science torch into their own communities. With the politicization of Covid-19, and the misinformation surrounding it, did any tension in the community arise in response to the science you shared? How has BioBus managed its own cultural literacy?

Latasha Wright: It’s important to understand the historical context that people are coming from, and understand where the misinformation is coming from. That also means taking responsibility for the science world’s lackluster communication. The first step, I think, is acknowledging the atrocities that Science has been a part of. People are not just going to go blindly and trust. The opioid epidemic is a good example of that. People trusted big science to give them the right advice.

Yewande Pearse: Yeah, people, especially people of color, have trusted science on more than one occasion and ended up regretting it.

Latasha Wright: I think you have to understand the history that people are bringing to the conversation. You may not know exactly where they’re coming from, but I think the best thing you can do is answer people’s questions and be open to the dialogue in an entirely non-judgmental way. People will make their own decisions, but your job is to give them the information so that they can make the best decisions possible. I’ve talked to people who specifically don’t want to be vaccinated but they also are taking all the precautions like socially distancing and wearing a mask and don’t believe that the vaccine contains a microchip.

Yewande Pearse: BioBus held a Student Town Hall series on racism in science during the 2020 uprisings, too. Who did you hope to target and how was it received?

Latasha Wright: I felt like it was a time where people were ready to have these types of conversations and I wanted to have them with people of color who are experts in the field. It was not just about racism, but racism in society, racism in disease, racism in medicine, and racism and science. It was really a labor of love for the people in our community and also for other people who are doing science outreach. It allowed us to have conversations about what type of language we’re using. It allowed people to see what allyship can mean and allowed students to really just ask questions. Some of them were practical questions like “What can I do if I see racism?”, while others were more expansive, like, “How has racism inhibited scientific discoveries?” One of the things that was really impactful for me was what we never really think about — how being racist affects non-black people or non-people of color. Trying to talk about racism, just with the people who already want to address it, is not going to achieve change by itself.

Yewande Pearse: Right, and to uplift your point about language. I like how BioBus talks about “untapped potential”.

Latasha Wright: Instead of “underserved,” “under-resourced,” let’s talk about the potential there. Let’s talk about how we all would benefit if everyone had access to the resources to make themselves the best version of themselves. Just think of what world we would be in if everyone was allowed to achieve their full potential.

Yewande Pearse: And I bet you have so many examples of kids who have really demonstrated that through their involvement with BioBus.

Latasha Wright: I’ll tell you about this one kid, Aaron. He went to our weekend programs, then he came to our summer camps, then he came to our after-school program, and then finally he was an intern with us. After going through all our programs, he wrote his college essay about how BioBus helped him really love science and inspired him to be a scientist.

“In elementary school I didn’t enjoy many topics we learned. I waited for Saturdays to attend BioBus. This was my habitat. Dissecting eyeballs to understand the different components that make it function, using microscopes to analyze micro-ecosystems, and exploring cells. In middle school, I spent summers attending BioBus camp exploring ecosystems, the East River and its many zooplankton, or the small environments throughout the city and the many factors that allow the environment to be stable. During the school year I struggled with public speaking, but in the summers, I presented in rooms full of strangers wearing my oversized lab coat, discussing my experiments and eagerly helping others.”

Aaron’s college application

Yewande Pearse: That must be so gratifying. It can be very easy for kids to lose interest in science at school if it’s not accessible enough to them. It’s easy to internalize not understanding science as just being bad at it. BioBus seems to catch kids at that delicate time and help shape a positive science identity. Going back to Covid and the uprisings, it also seems like BioBus recognizes politics as an important part of science literacy and also offers the tools needed to navigate science within the context of politics.

Latasha Wright: We’ve always been activists, right? And what we’re trying to do is level the playing field, but most importantly we’re building critical thinkers who are not afraid to engage in the scientific process. That right there benefits everyone: Being able to think critically and not see something like your prescriptions and be afraid to ask your doctor questions. Being able to take care of your parents when they get older because you’re able to understand what the doctors are saying, what the nurse is saying, and understand what is happening, or the side effects of a drug. This is fundamental knowledge that you need for your everyday life to be successful as a human being in this world and just live your best life.

Yewande Pearse: Right, science literacy is so relevant to all our lives, but many people feel excluded from that information. Not just as individuals, but as communities.

Latasha Wright: That knowledge allows you to engage in the political process and things that really impact your community. Once you start thinking critically and not being afraid when you see science then you can start making these decisions and changing the neighborhoods that you live in. The ultimate goal is that when a new science facility comes into your neighborhood, you don’t look at it as something negative; you look at as an opportunity for everyone to get a job at this place and get better economic outcomes for your kids and to be able to say “hey, I’m a scientist and I work at this place that it’s helping the world be a better place.”

Yewande Pearse: Right, that’s what you mean by building a science identity.

Latasha Wright: Humans are so innovative; we just need to be able to make sure that everybody has an opportunity to really be the best version of themselves. That’s it.

Yewande Pearse: Absolutely, it’s about equity. Science Literacy is an important part of life literacy. How is it trying to bring this important message back to students IRL? How are you navigating that?

Latasha Wright: Last year, the kids really had Zoom fatigue and they just couldn’t take it anymore and so we developed an internal decision-making body to figure out when and how we could deliver programs in person again safely. In May 2021, we brought science back in person, followed all of these wonderful safety protocols and we were able to serve tons of kids all year. We have had zero Covid transmissions between us and our community. In New York, Omicron really spiked in January and so we went back online again. But now that the spike is going down, February fourteenth will be our first day back in person.

Yewande Pearse: That’s amazing. I’m blown away by the work that you do with BioBus, and I really appreciate the time you took for this interview.